How the integration simplifies document management in Cloud PLM

Pioneering technologies and digital innovations are shaping today’s economy. Seamless collaboration within companies is an essential factor for success. Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) supports this and helps increase efficiency. This is where the integration of Microsoft Office for the web™ in Cloud PLM comes into play. The integration of PLM systems and Microsoft Office not only promises an optimized way of working but also a smooth workflow that takes collaboration and productivity to a whole new level.

In this interview, André Guldi, Product Manager Cloud at CONTACT Software, explains the differences between document management with MS Office and in Cloud PLM, as well as the benefits of integrating Office for the web™.

André, how does document management differ in MS Office and Cloud PLM?

AG: MS Office has become the standard for creating documents, spreadsheets, and presentations because of its ease of use and extensive editing capabilities. However, documents are usually stored at the file level, which can lead to an unstructured data landscape. There is often no proper version control, leading to confusion and uncertainty about which documents are up-to-date. Many copies of the same document can be in circulation at a company, which makes collaboration and traceability difficult.

In Cloud PLM, this is different: its document management functionality offers a comprehensive solution. It establishes a “Single Source of Truth” for any type of document – a central, reliable storage location for documents. Managing metadata and file attachments allows for the structured organization and quick identification of documents. Additionally, extensive versioning, release workflows, and access control enhance document control. Search functions not only scan file names but also metadata and, using full-text search, even the content of the files. This simplifies finding documents and saves valuable time. Another significant advantage of document management in Cloud PLM is audit-safe storage. It is clear to users at first glance which document is currently valid, thus avoiding confusion or incorrect use.

What is Microsoft Office for the web™?

AG: Microsoft Office for the web™ (formerly Office Web Apps) is a web-based application that facilitates working with Office files. It allows users to open Word, Excel, OneNote, and PowerPoint documents directly in a web browser. The device used only requires a supported browser, an active internet connection, and users need a suite license. This allows them to use the full functionality of the web-based Office applications. This license not only allows them to gain access to documents but also to edit and share them with others – conveniently through the web browser without installing the Office Suite on their computer.

What are the benefits of integrating Office for the web™ into Cloud PLM?

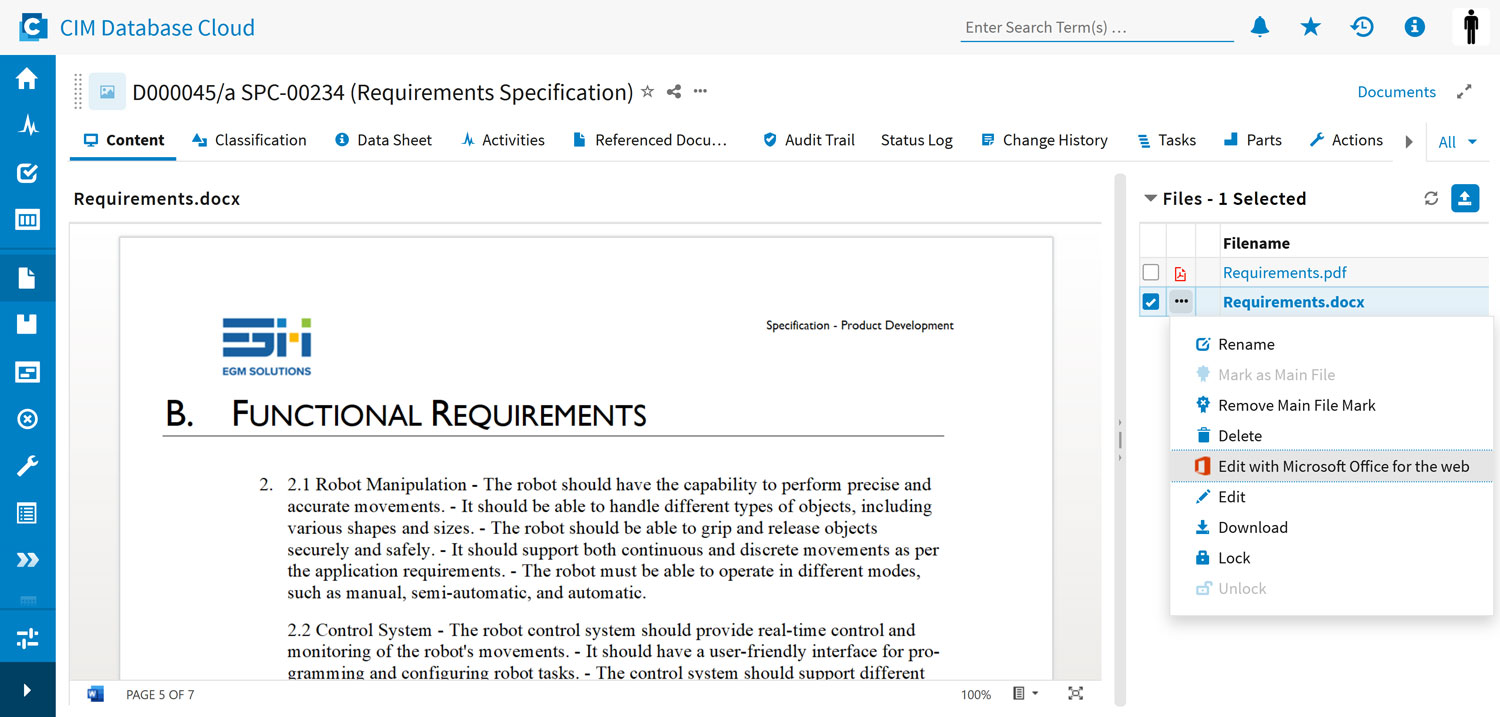

AG: Microsoft Office for the web™ is seamlessly integrated into the Cloud PLM web interface. This allows users to create, view, and edit Office documents directly without the need to save them separately. They are saved in the Cloud PLM file storage, also known as Blobstore. This feature allows multiple people to work on the same document simultaneously without relying on local installations of MS Office.

A key feature is that only a single file exists, which simplifies file management and ensures a clear structure. The solution combines the advantages of an online Office editor with centralized and legally compliant document management in the PLM system: avoiding additional programs, eliminating file transfers, and enabling collaborative editing with version tracking, release workflows, and access control. This ensures efficient and secure document management.

What makes the connection between Office for the web™ and CIM Database Cloud special?

AG: CONTACT Software is the first software provider to offer the Office for the web™ integration in a Cloud PLM system. To edit an Office document in CIM Database Cloud, customers need an Office for the web™ suite license.

Conclusion

Microsoft Office for the web™ provides companies with an efficient solution for document management. It enables users to directly create, view, and simultaneously edit Office documents. The integration saves files directly in the Cloud PLM file storage, promotes collaborative work without local MS Office installations, and ensures a clear structure through a single file. This solution combines the advantages of an online Office editor with centralized document management in the Cloud PLM system, including versioning, release workflows, and access control for efficient and secure document management.

Discover CIM Database Cloud now – the first Cloud PLM system that enables the seamless integration of Microsoft Office for the web™.